Keystone Mining

From Gold to Granite

The town of Keystone, SD was established in the late 1800s at the end of the Black Hills Gold Rush era. Today, it is a tourist destination, owing to its fame to the carving of Mount Rushmore. But the town existed years before the monument was even conceived. This paper is an attempt to look at the beginnings of Keystone, how it developed, and how Mount Rushmore changed this once-booming gold rush town into the tourist town it is today.

Although mining brought settlers to Keystone and helped the town to prosper, Mount Rushmore National Park has helped the town to survive. The development of Keystone could be defined in phases. The first was the initial discovery of mineral deposits, mainly gold, in the region. The discovery of gold led to a flood of prospectors – all hoping to get rich quick. Next was the establishment of the town of Keystone itself, named after the Keystone mine discovered in 1891. This second phase of development saw Keystone prosper, decline, and begin to recover. The third phase in the development of Keystone occurred during the carving of Mount Rushmore. This project had a big impact on the lives of the citizens of the town, from the establishment of electric power to the jobs it created. The fourth and current phase of Keystone is the Keystone of today – no longer a mining town, but a tourist town that prospers thanks to the carving of Mount Rushmore.

The first phase was defined by the entry of prospectors into the region. Gold was first discovered in the area around present-day Keystone, SD in 1875 in Battle Creek. Miners soon started to flood the area and Harney City, named after nearby Harney Peak, was established. According to the New York Tribune, about 300 miners were working in the area that year. Annual figures for placer gold or gold panned from the streams, from the Harney area are in the millions of dollars.

The first settler to the region was a man by the name of Fred J Cross who built a cabin in Buckeye Gulch in 1877.

As more people came into the area, the town started to develop. On January 22, 1877, L Field Whitbeck, in a letter to the Sidney Telegraph of Sidney, Nebraska wrote, “These districts are now well-settled and new arrivals occur daily. This deletable burg, located twenty miles northeast of Custer, now contains twenty-five cabins and about seventy-five residents, including now two of the gentler sex, bless, their hearts, who are here visiting.” And again on May 22, 1877, he wrote, “Harney City now has one store and one saloon but a second store will open soon. It also has a sawmill owned by Bock and Company.” Through Whitbeck, the development and growth of the town are visible.

Women were not allowed to enter the area until two years after the camps were established. The first woman settler arrived in 1877. Her husband was a carpenter working in the area, and, as he was not expecting her, was delighted to see her. The rest of the miners were delighted as well. With her, she brought a cow and the miners were able to purchase milk. However, her stay was short as her husband’s services were needed in the building boom in Hayward a few months later.

In 1883, just as the placer mines started to play out, the Harney Hydraulic Gold Mining Company was formed. The company provided a way to dig through the gravel beds using hydraulics. The owners, A.J. Simmons, William Claggett, and T.H. Russell spent around $2,000,000 in setting up flumes to bring in water to work their six miles of claims on Battle Creek. Unfortunately, the operation never made a profit, and in a year-and-a-half was sold to a company in Milwaukee, never to be opened again.

The Etta Mine was discovered around 1883 by Dr. S.H. Ferguson just south of present-day Keystone. Alex Madill and Major A.J. Simmons bought into the mine soon after. Starting as a mica mine, it quickly gained notoriety after Simmons sent a sample of cassiterite, a tin ore, to San Francisco to be evaluated. It was reported that Etta was one of the richest tin mines known at that time. After the reports were made, a group of American and English businessmen joined together to form the Harney Peak Tin Mining, Milling, and Manufacturing Company. They purchased 1100 claims, including the Etta Mine, at a price of just over $2,000,000. The total area covered over 5000 acres.

The settlement that grew around the area became known as the Etta Camp. Lumber used at the settlement was originally purchased from a mill on Iron Creek in Custer County, but after changing owners, it was moved closer to the camp. Houses were built and families moved in. However, Etta failed to earn a profit. It went into receivership and shut down in 1886. It was reopened in 1898 after 30 tons of spodumene were shipped to Omaha, Nebraska for experiments. The evaluation of the mineral proved it was a valuable source of lithium. Reinbold and Company, the group responsible for the experimentation, quickly leased the mine. Five hundred tons of spodumene were mined in 1899; 700 tons the next year. These figures made Etta the biggest spodumene mine in the United States.

In 1905, when the lease was over, it was not renewed. Instead, the Etta Mine was leased by the Standard Essence Company or, as it was later known, the Maywood Chemical Works. In 1908, the company purchased the Harney Peak Tin Company. The mine was worked continuously until 1936, and sporadically after that until at least 1955. By 1968 the mine had closed for good.

The discovery of the Keystone Mine in 1891 by William Franklin, Thomas Blair, and Jacob Reed began the second phase in the development of Keystone. This was a rich mine, at one time producing as much as $2.50 in one pan of crushed ore. In 1892, the Keystone Mine opened a twenty stamp mill for the purpose of crushing the ore. In 1893 it was sold to a group from St. Paul called the Keystone Mining Company. The Keystone Mine was purchased by the Holy Terror Gold Mine in 1897.

Mining did not stop with the Keystone Mine. On June 28, 1894, Franklin and his adopted daughter Cora Stone discovered gold at the base of Mt. Aetna. This mine would become one of the richest in the country. The story of how it got its name is best told by Martha Linde:

They lived together in harmony until those occasions when William Franklin would feel the need to indulge his taste for strong liquor and would leave for a nearby town. At these times he remained absent until his wife, knowing from past experience where to look, would go in search of him. When she found the right saloon, there he would be, slightly under the weather, telling the other occupants tales of his wonderful mining prospects. Upon sighting William, his wife would rush in, grab him by the sleeve, and state in a loud and angry voice her opinion of his actions. He would always come along meekly, stating with a sheepish grin to bystanders, “Ain’t she a Holy Terror?” After he found the phenomenally rich ore and his partner suggested he name the mine after his wife, it became not the Jennie, but the Holy Terror Gold Mine.

Together with his friend, Tom Blair, the two began digging the Holy Terror shaft mine. By the end of the first year, the men had dug fifty feet down and found ore worth $500 a ton. At ninety feet, they offered a one-half interest in the mine to investors John J Fayel and Albert Amsbury if they would build a five stamp mill. By the end of 1894, over $40,000 in gold had been removed from the mine. The Holy Terror is reported to have had a weekly take of between $10,000 and $70,000, not including what the gold miners took out in their boots and lunch pails.

In 1895, the Holy Terror was sold to John S. George and Charles M. Kiff of Milwaukee and J.J. Foyce of Keystone. Two years later, the mine was again sold, this time to men from Rapid City. These new owners continued to work the mine sinking it to new depths. They also bought the Keystone Mine and in 1898 joined the two with a drift, therefore, enabling them to lift the Keystone ore through the Holy Terror shaft.

Although highly profitable, these mines were also extremely dangerous. In 1896, there was a fire at the Keystone. When the ever-constant sound of the stamps suddenly stopped, people came running. They quickly formed a bucket brigade to the creek. After hours of hauling water, the miners trapped inside were able to crawl out. There were no fatalities. However, miners at the Holy Terror weren’t so lucky. In 1901, three men were killed from gases forced through an air hose by a faulty compressor. The company was sued and, two years later, forced to close as the court ruled in favor of the miner’s families. The owners lost everything and the mine was sold at auction to Mr. Lee.

The Holy Terror was again sold in 1906 to Mr. Collins and Mr. Morgan. The mine, having sat for several years unused, had filled with water. The new owners tried to pump it out but discovered the shaft logs had worn out and broke easily, and that the mine had caved in at various locations. When they reached 400 feet, Collins sold his share to Morgan, who worked for a while longer. When his money dried up, the mine refilled. There are no records showing mining was done by these two.

The Holy Terror only reopened again for a few years from 1938 until 1942. It is rumored that there is still much more gold down there. Overall, the Holy Terror and Keystone Mines produced $1,284,689 between 1894 and 1903.

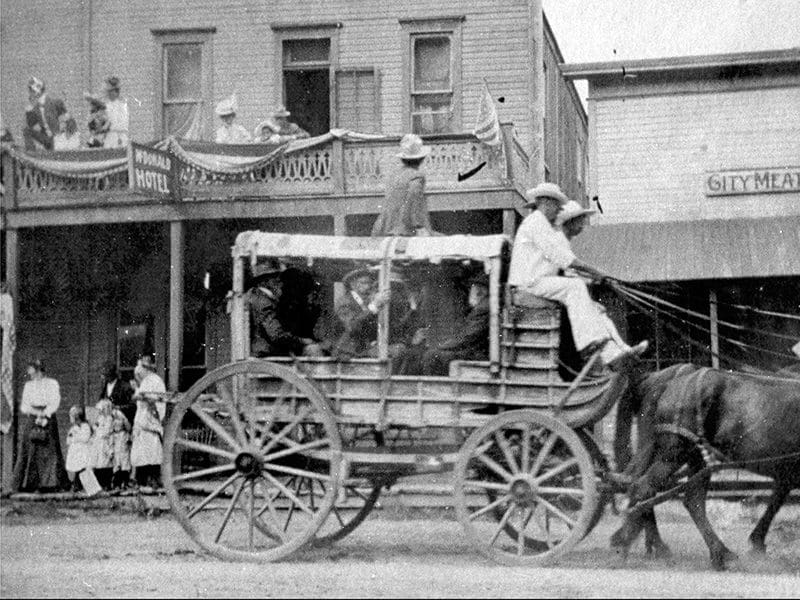

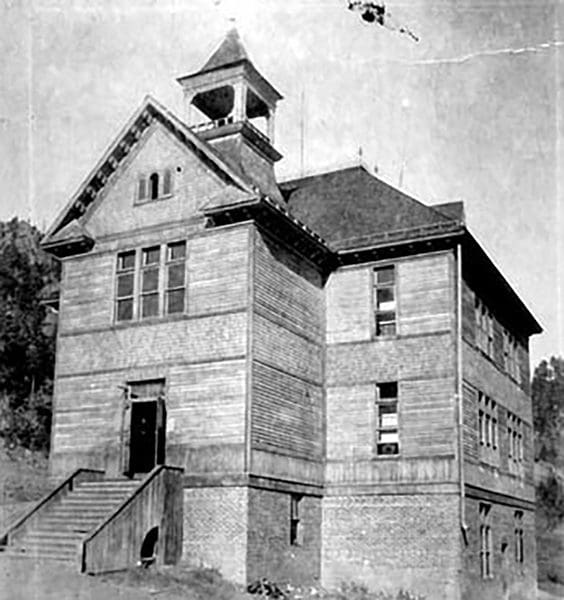

The city of Keystone is said to have gotten its name from the Keystone Mine. The theory was that the town is halfway between the northern and southern Black Hills, therefore the keystone of the area. As new claims were discovered, more people came to the area. Saloons and hotels were built first. Then, merchants and businessmen, from carpenters to bakers, came from everywhere to fill the needs of a growing community. Churches and schools came at a later date. The church was originally held at Baldwin’s Hall, above Jim Baldwin’s pharmacy. A small log cabin served as the first school. The school situation improved when, in 1895, Willis Bower, with his wife Augusta and her daughter, built a house in Keystone. He left the first floor open as one big room to use as a private school. On June 29, 1895, the citizens of Keystone held a meeting to consider the organization of a church. At the second meeting held on August 11, the First Congregational Church of Keystone was officially formed. Reverend James A. Becker was hired to be minister for six months for a total of $200. The Bower school was rented at a rate of three dollars a month so the church could hold meetings and Sunday school.

Together with his friend, Tom Blair, the two began digging the Holy Terror shaft mine. By the end of the first year, the men had dug fifty feet down and found ore worth $500 a ton. At ninety feet, they offered a one-half interest in the mine to investors John J Fayel and Albert Amsbury if they would build a five stamp mill. By the end of 1894, over $40,000 in gold had been removed from the mine. The Holy Terror is reported to have had a weekly take of between $10,000 and $70,000, not including what the gold miners took out in their boots and lunch pails.

In 1895, the Holy Terror was sold to John S. George and Charles M. Kiff of Milwaukee and J.J. Foyce of Keystone. Two years later, the mine was again sold, this time to men from Rapid City. These new owners continued to work the mine sinking it to new depths. They also bought the Keystone Mine and in 1898 joined the two with a drift, therefore, enabling them to lift the Keystone ore through the Holy Terror shaft.

Although highly profitable, these mines were also extremely dangerous. In 1896, there was a fire at the Keystone. When the ever-constant sound of the stamps suddenly stopped, people came running. They quickly formed a bucket brigade to the creek. After hours of hauling water, the miners trapped inside were able to crawl out. There were no fatalities. However, miners at the Holy Terror weren’t so lucky. In 1901, three men were killed from gases forced through an air hose by a faulty compressor. The company was sued and, two years later, forced to close as the court ruled in favor of the miner’s families. The owners lost everything and the mine was sold at auction to Mr. Lee.

The Holy Terror was again sold in 1906 to Mr. Collins and Mr. Morgan. The mine, having sat for several years unused, had filled with water. The new owners tried to pump it out but discovered the shaft logs had worn out and broke easily, and that the mine had caved in at various locations. When they reached 400 feet, Collins sold his share to Morgan, who worked for a while longer. When his money dried up, the mine refilled. There are no records showing mining was done by these two.

The Holy Terror only reopened again for a few years from 1938 until 1942. It is rumored that there is still much more gold down there. Overall, the Holy Terror and Keystone Mines produced $1,284,689 between 1894 and 1903.

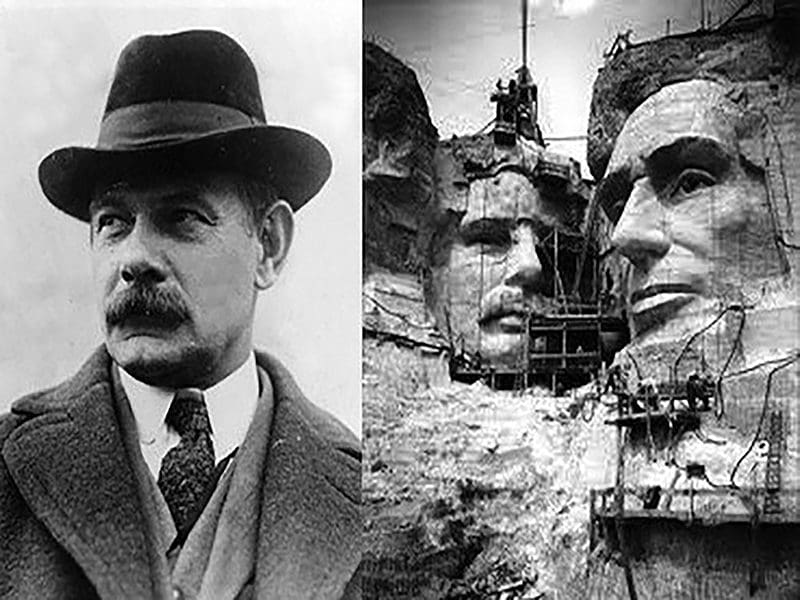

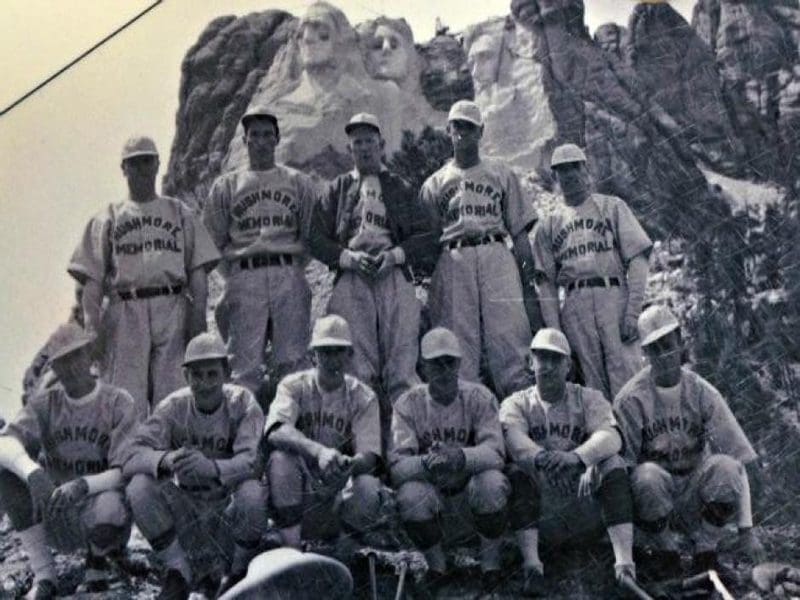

The beginning of the third phase of Keystone dealt with the carving of Mount Rushmore. In the mid-1920s. South Dakota State Historian, Doane Robinson, was promoting tourism in the state. He suggested carving the granite spires in the Black Hills into figures from South Dakota’s history. In 1924, he invited popular sculptor, Gutzon Borglum, to evaluate the feasibility of the project. Borglum was born of Danish immigrants in 1867 in Bear Lake, Idaho. Growing up he discovered a talent for the arts and attended art school in Paris. He quickly received notoriety in Europe and the United States for his paintings and sculptures. During the early 1920s, he worked on Stone Mountain, a monument to the Confederate heroes of the Civil War, in Georgia. In 1925, he was fired from the project over funding issues. Before leaving, he destroyed both his work on the mountain and his prepared models.

When Borglum first toured the Hills, he was accompanied by his 12-year-old son, Lincoln Robinson, and South Dakota Senator Peter Norbeck, who was eager to help get the project started. He convinced them that carving heroes on the spires in the Hills was not the best idea and that the figures should be of national importance. He also rejected the location Robinson had chosen. He chose a large granite outcropping near the city of Keystone the locals called Rushmore. The name Rushmore came from a New York attorney who, when visiting the area, asked the locals what the mountain was called. They responded with, “Hanged if we know! Let’s call the damned thing Rushmore.” The name stuck.

Borglum held his first dedication of the carving on October 1, 1925, at Doane Mountain across the valley from Rushmore. Norbeck contributed $500 to the event; the Rapid City Commercial Club donated $1000. Borglum was a natural showman. His ceremony included a band, speakers, flag-raising, Sioux Indians, and a twenty-one gun salute. The newspapers and audience of 3000 loved it. However, the money did not come pouring in. After Borglum’s trouble at Stone Mountain, no one wanted to invest in what was considered to be a risky undertaking. In the end, he requested $50,000 from Rapid City to start the project, but as they had previously been promised that they would not have to contribute, they did not do so.

When President Calvin Coolidge decided to spend his summer in Custer State Park in 1927, Borglum seized the opportunity to promote Mount Rushmore. He asked the President to speak at a second dedication ceremony. In honor of the President’s arrival, Borglum had tree stumps blasted out of the right-of-way on a road to Mount Rushmore. President Coolidge showed up at the ceremony on horseback sporting a ten-gallon hat and cowboy boots. The speech he made was reported to be his best ever. He proclaimed that the monument “deserved the sympathy and support of private beneficence and the national government.” Afterward, he handed Borglum a set of drills, which Borglum promptly used on the mountain, officially starting the carving. President Coolidge was also asked to write an inscription for the bottom of the monument, which was never carved.

After this event, money started pouring in. The most notable contributors included Homestake Mining Company of Lead, South Dakota, which built three rail lines to the region; Herbert Myrick of Boston, a publisher of agricultural journals including The Dakota Farmer, donated $1000; and Charles Rushmore, who was flattered his namesake was to become famous, donated $500. By July of 1927, Borglum had raised $50,000.

With Mount Rushmore underway, monumental changes came to Keystone. A major benefit to the town was the addition of roads. The roads to Keystone up to this point were small, dirt roads, subject to the weather and oftentimes impossible. The most reliable way to bring in supplies was a spur of the Chicago Burlington and Quincy railroad, built-in 1900, connecting Keystone to Hill City. From there, a team and wagon transported the supplies the remaining three miles to Mount Rushmore. After a time, Borglum convinced the state to build a road from Rapid City into Keystone, making the delivery of supplies and travel to and from Keystone easier. This new road bypassed the town’s main road and ran through Buckeye Gulch. Today this road is known as Highway 16A and is the main artery into the town. Another road built on account of Mount Rushmore was Iron Mountain Road. Planned by Norbeck, this road wound its way from Custer State Park to Keystone and was built to offer spectacular views of Mount Rushmore, framed by tunnels.

Another notable benefit to Keystone was the addition of electric power. Prior to Mount Rushmore, Keystone’s mines were powered by steam-driven engines, fueled by the forests surrounding the town. Between 1927 and 1928 the conversion to electric power started with a gift to Rushmore from Samuel Insull of Chicago. Insull loaned Borglum a three-cylinder diesel engine to power the drills needed to carve the mountain. This first generator was housed near the railroad depot in town, three miles from Rushmore, because it was impractical to transport it, and the fuel needed to run it, up the mountain. The diesel fuel used to run the engine was produced in Casper, WY and transported to Keystone via the railway. In order to transport the power to Rushmore, pine trees were stripped of their branches and converted into power poles.

The lines were draped from tree to tree all the way up the mountain. As it turns out, the generator Insull loaned Borglum was not a good one. The cost of running it was high, as it took two men to keep it running. One time the engine actually exploded, causing injury to one of the workers. Its use was therefore discontinued after the first year.

At about the same time, Keystone Consolidated Mines built their own power plant near the Holy Terror Mine. The mines that were currently in operation were supplied with power from the new plant. This power plant served double duty as it also severed the community. After the explosion of the Insull generator, John Boland, financial manager at Mount Rushmore, purchased power from Keystone Consolidated. When the company built regular power lines to the mountain, Borglum approached A.I. Johnson, an employee of Keystone Consolidated, and told him, “The power line looks monstrous crossing those hills. Don’t you know that nature abhors a straight line?” To which Johnson replied, “Electricity doesn’t follow beautiful curves like you artists make.” The Keystone Consolidated Mines ran into financial trouble when the Keystone Mill burned down in 1930. The company closed their mines, lost two generators to receivership, and gave a compressor to Mount Rushmore. Afterward, the company continued operation at the plant, renaming itself as the Battle Creek Power Company.

Power in Keystone was subject to the schedules of the mines and Mount Rushmore. During the day, when the men were working on these projects, the power was on. At night, power was shut off at 11 pm with a warning five minutes before the hour. When both the mines and Mount Rushmore were not operating, the power plant was not run during the day, with the exception of Monday mornings when the women of the town did their laundry. It wasn’t until 1939 that Keystone had full-time power.

On March 6, 1941, Gutzon Borglum passed away. His son Lincoln added some finishing touches on Mount Rushmore, using up the remaining funds, then closed the operation a few months later. The shrine stands today as a testament to all who worked there.

With the end of the carving, we come to the current phase of the town of Keystone. Since 1941, Keystone has thrived on tourism. Souvenir shops sprang up along Borglum’s new road, almost to the base of Mount Rushmore. Many attractions have opened up over the years to entertain guests during their visit. Some of the more notable are the Black Hills Central Railroad, or 1880 Train, which opened in 1957 and travels between Keystone and Hill City on the Chicago Burlington and Quincy spur; Big Thunder Gold Mine, providing tourists a glimpse of the past through what was once a working gold mine; the Rushmore Borglum Story, a museum that tells the story of the carving of Mount Rushmore and of Borglum himself; a wax museum featuring the Presidents of the United States; miniature golf course named after the Holy Terror Gold Mine; and many other attractions.

As of 2013, the population of Keystone is 327, a far cry from 2000 it once supported. After mining left the area, Keystone, like all other mining towns, should probably have died out, but with the addition of Mount Rushmore, this small town is thriving and should be around for many years to come.

Works Cited

- Bower Van Nuys, Laura. The Family Band: From Missouri to the Black Hills 1881-1900. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1961.

- Clark, Badger. "The Mountain that had its Face Lifted," in The Black Hills, ed. Roderick Peattie (New York: The Vanguard Press, 1952), 222.

- Fielder, Mildred. A Guide to Black Hills Ghost Mines. Aberdeen, SD: North Plains Press, 1972.

- Hayes, Bob. "Centennial-The Keystone Congregational Church, or The United Church of Christ (U.C.C.)." In Keystone Area Historical SocietyWestRiver History Conference September 14, 15, & 16, 1995

- Papers, 341-356. Keystone, SD: Keystone Area Historical Society, 1996.

- Hayes, Bob. "The Power Behind the Men of Mount Rushmore." In Keystone Area Historical SocietyWestRiver History Conference September 14, 15, & 16, 1995 Papers, 341-356. Keystone, SD: Keystone Area Historical Society, 1996.

- Linde, Martha. Rushmore's GoldenValleys. Keystone: Permelia Publishing, 1988.

- Rezatto, Helen. Tales of the Black Hills. Aberdeen, SD: North Plains Press, 1983.

- Tallent, Annie D. The Black Hills of Last Hunting Grounds of the Dakotahs. Sioux Falls, SD: Brevet Press, 1974.

- Zeitner, June Culp and Lincoln Borglum. Borglum's Unfinished Dream: Mount Rushmore. Aberdeen, SD: North Plains Press, 1976.